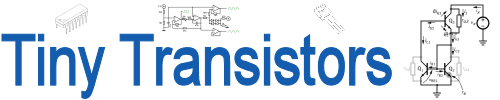

I recently came across this funky looking thing. Left behind by a dishwasher repairman, it’s a pressure sensor from a dishwasher made by Marquardt, a German manufacturer of sensors, switches, pumps, lights, and various other components for industrial and automotive applications.

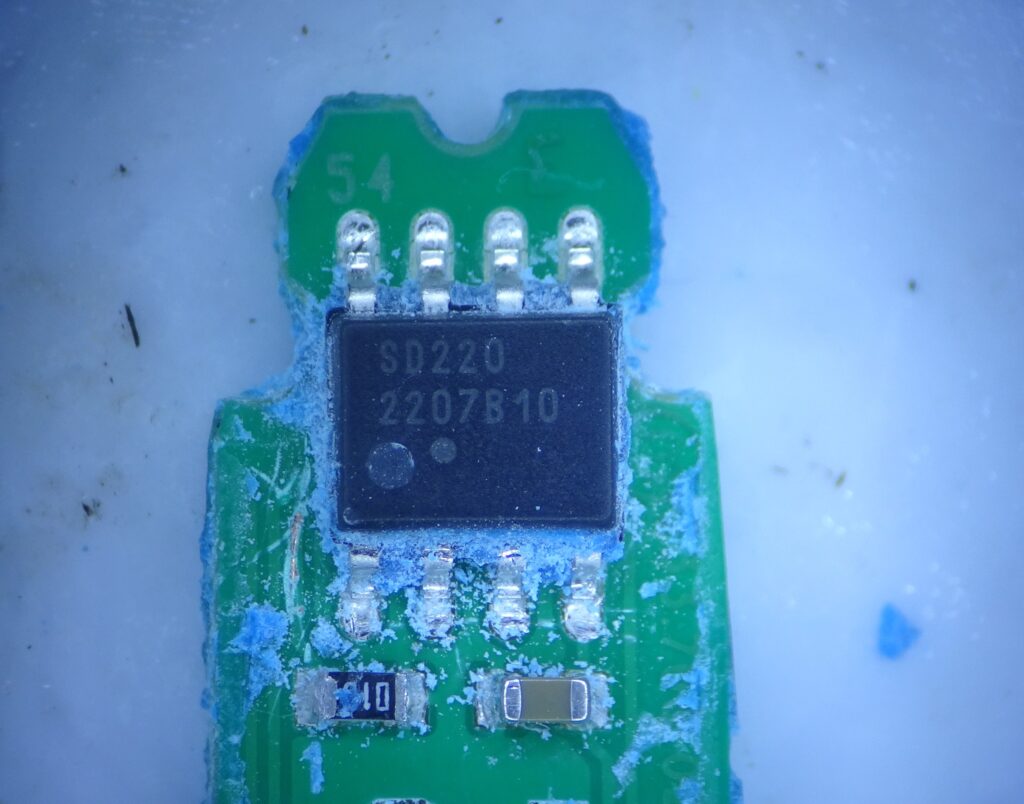

There’s a whole bunch of numbers printed on the housing: the first two lines are production line information (made on day 4, week 30, 2022), the line after that is the end user’s part number (either “A00055407” or “A00055408”, with the last number having been rubbed off this specimen), and the final line is Marquardt’s part number (2066.0303, meaning a 2066 series sensor with a frequency output).

The black bit on the left is the water inlet. The white bit on the right has a three-pin connector to interface with the dishwasher’s computer.

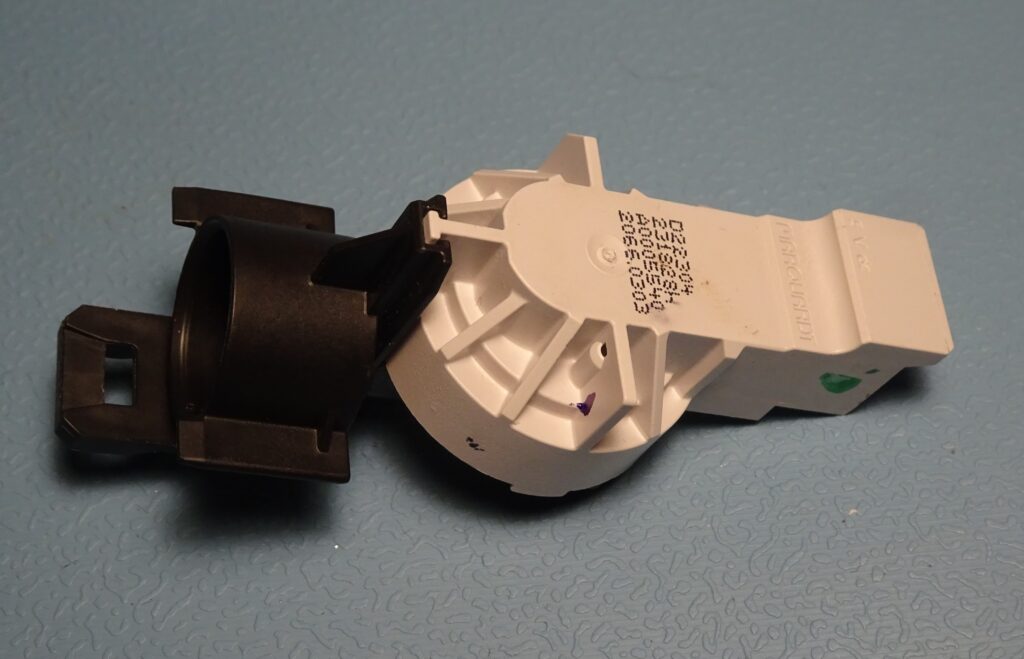

If we disassemble the two pieces, we can figure out how the pressure sensor works. The water pushes against a rubber diaphragm that has a little magnet in the middle. The resulting up-and-down motion of the magnet is detected by a magnetic sensor in the white part.

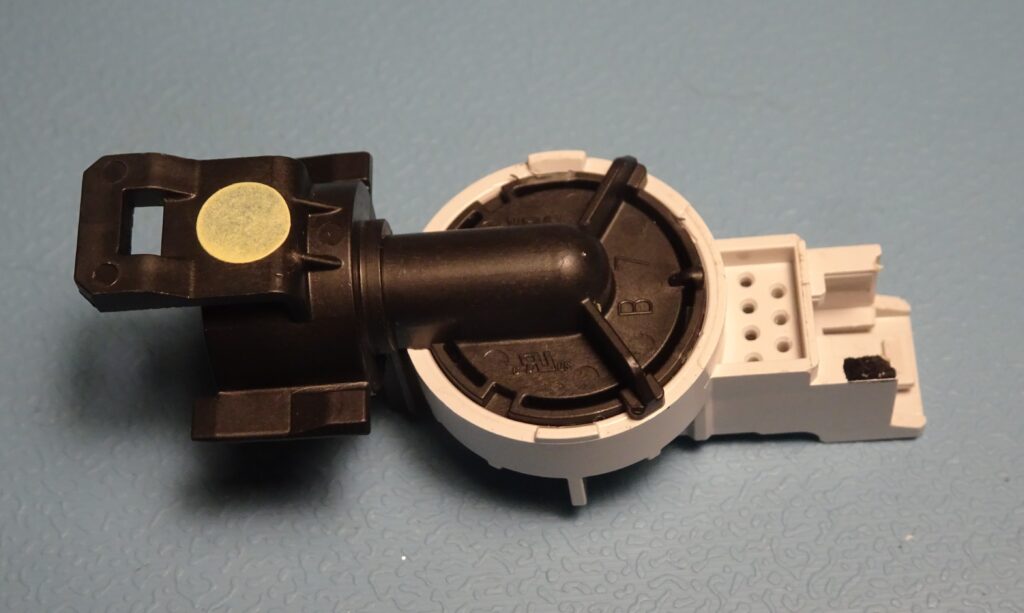

Inside the white part we find this little PCB. It was completely covered with a blue gooey substance. The connector is helpfully labelled “VDD-GND-OUT”. Upon connecting 5 V between VDD and GND, the OUT pin outputs a 46 Hz square wave. It doesn’t change at all if I bring the magnet closer, however; perhaps that was why this part was replaced.

The chip is apparently called “SD220”, but I can’t find any information about such a chip. Most likely it’s a custom part specially made for Marquardt.

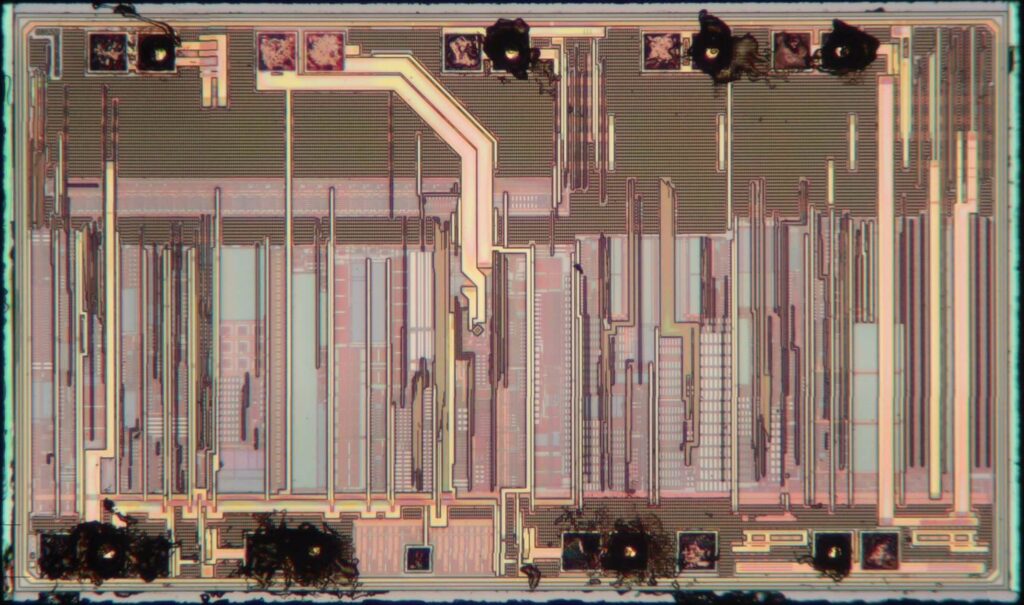

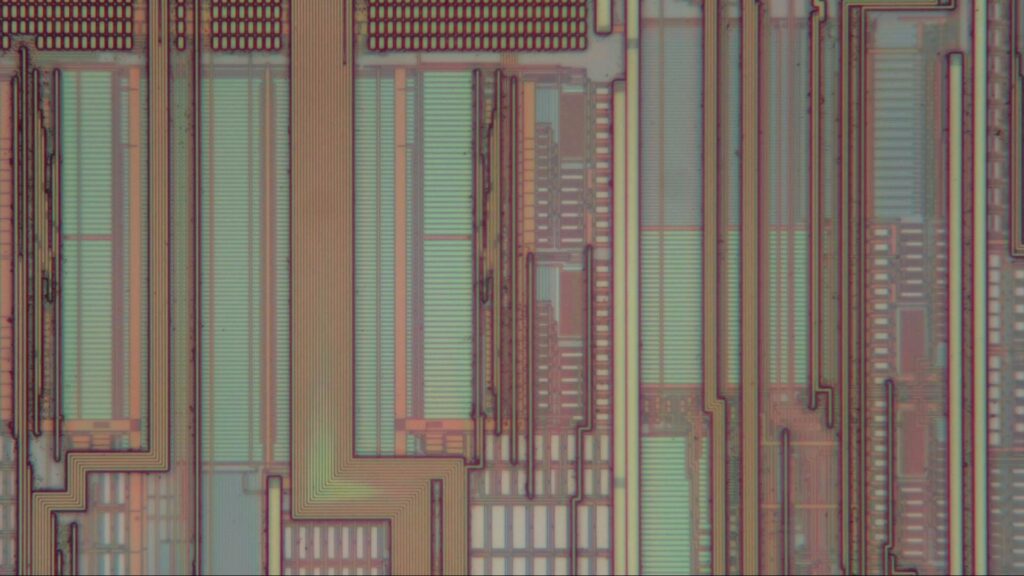

This is what the chip looks like on the inside. It’s interesting to see how many wires are oriented in the vertical direction. Right in the middle of the chip is some kind of sensor, connected to two bond pads on the upper row through two thick metal traces. The top third of the chip seems to be mostly covered with digital circuits, with the rest mostly analog stuff.

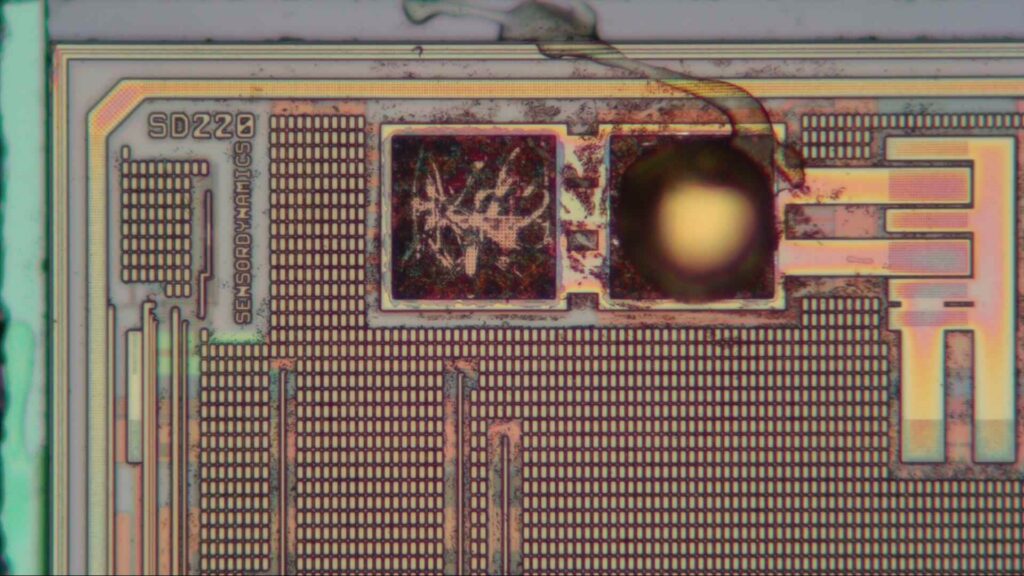

In the top-left corner we find the SD220 part number again, along with the manufacturer’s name. SensorDynamics was an Austrian semiconductor company specialising in MEMS devices for automotive applications, but apparently also made magnetic sensors. The company was founded in 2003 and acquired by Maxim in 2011. The only reference I can find to this device is a product discontinuance notice mentioning that the SD220+123 can no longer be ordered after 30 April 2019 because the “Part can no longer be manufactured”. Apparently Marquardt bought a big bunch of these chips, given that this pressure sensor was made three years later.

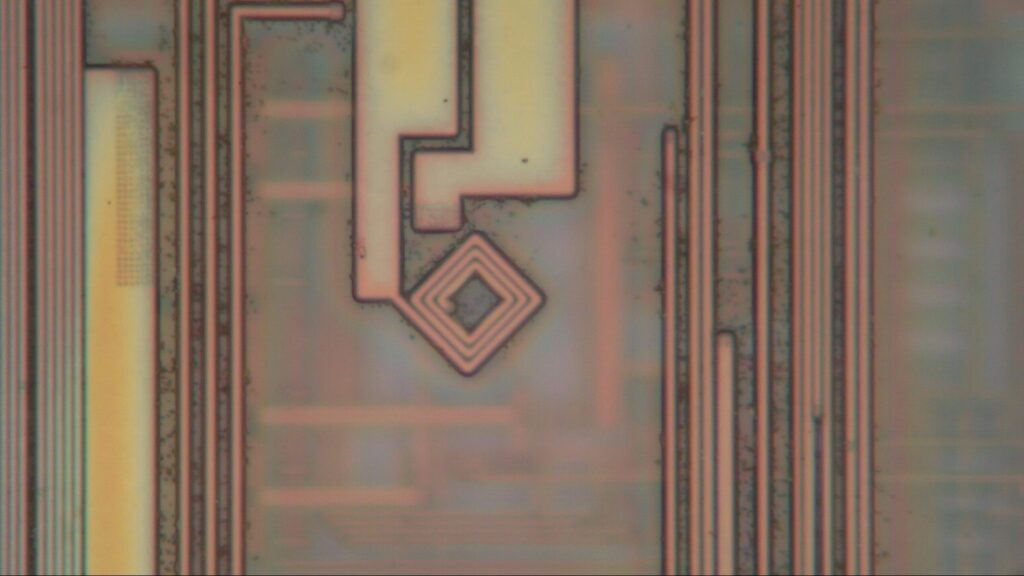

Here is a closer look at the centre of the chip. There is a small square inductor at a 45-degree angle, connected to the two wires that go to two bond pads. Note how the wires cross right before they reach the inductor. This is probably done to cancel out the magnetic field being generated by the two wires and to concentrate the field into the coil.

The coil itself is just that: a few loops of wire. A coil can be used to sense changing magnetic fields, but that doesn’t make sense in our pressure sensor because it should presumably be able to detect static fields as well. I suspect that this chip has some sort of magnetoresistive sensor inside, with the coil being used for compensation or calibration purposes.

We can see below the coil if we slightly change the microscope’s focus. The grey area underneath the coil might be something like an anisotropic magnetoresistive (AMR) or giant magnetoresistive (GMR) sensor. Integrating such a sensor would require a special sensing layer to be added to the manufacturing process.

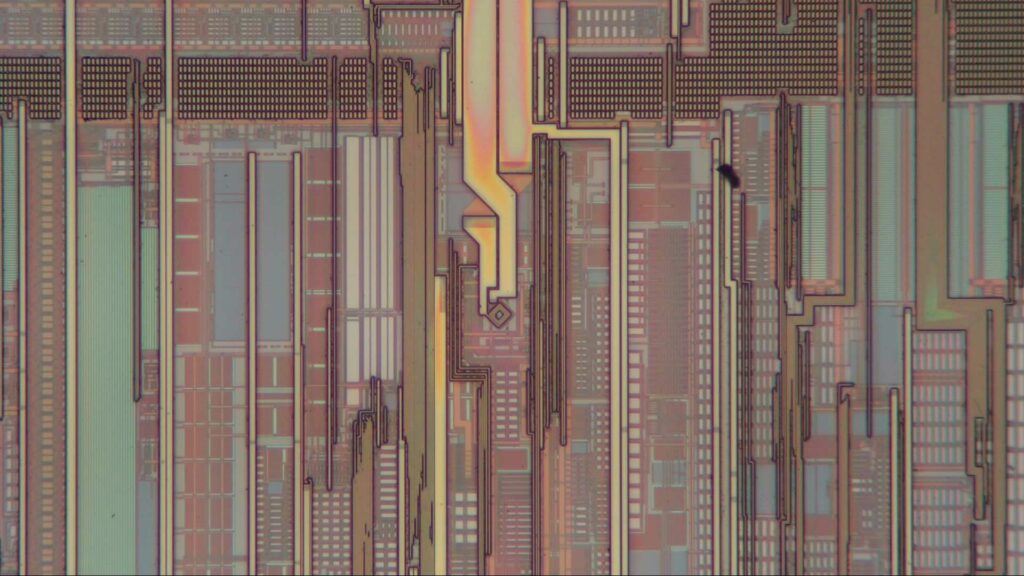

Most of the rest of the chip consists of analog circuits like these. We can see light-blue resistor stripes as well as lots of transistor arrays (the pale rectangles). These form circuit blocks like analog-to-digital converters, oscillators and voltage references. To be honest, I’m a bit surprised by how much circuitry there is. I was expecting to find a reasonably large sensor surrounded by some basic circuits, but it appears to be the other way around: a small sensor with lots of circuits.